Taylor, Mississippi

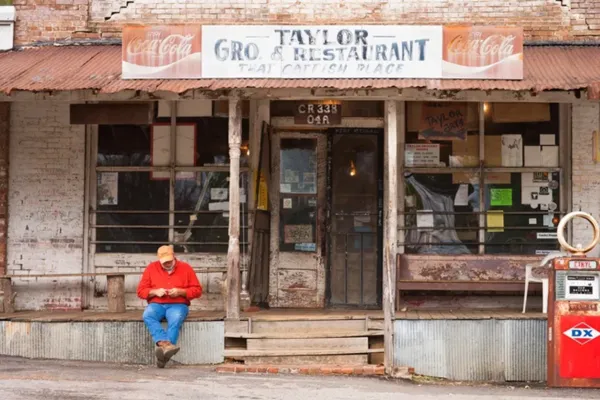

From modest beginnings as a pioneer settlement to its rise and fall with the railroad and King Cotton, Taylor endures and is now, as Faulkner put it, a “postage stamp of native soil” that attracts visitors and new residents from all over the world who come for its famous food, music and arts scene and bucolic lifestyle.

Board of Aldermen

Mayor

Shawn Edwards

Telephone: 662-816-7841

Email: [email protected]

Town Clerk

Ashley Atkinson

Telephone: 662-236-7551

Cell: 662-832-2087

Email: [email protected]

Deputy Town Clerk

Mark Woods

Telephone: 662-816-6674

Email: [email protected]

Town Attorney

Chris Latimer

Telephone: 662-232-3208

Email: [email protected]

Town Engineer/

Floodplain Administrator

Jeff Williams

Telephone: 662-236-9675

Email: [email protected]

Planning Consultant

Judy Daniel

Telephone: 301-906-7833

Email: [email protected]

Building Official/Inspector

Scott Allen

Telephone: 662-801-7787

Email: [email protected]

Maintenance/Streets

Keith Stewart

Telephone: 662-202-4882

Email: taylortownhall@att.net

Lyn Roberts (Mayor Pro Tempore)

Telephone: 662-832-5026

Email: [email protected]

Bill Taylor

Telephone: 662-473-6104

Email: [email protected]

Jim Hamilton

Telephone: 662-234-2929

Email: [email protected]

Tim Carter

Telephone: 662-236-7551

Email: [email protected]

SHARE THIS SITE

Planning Commissioners

Anndy Veazey, Chairman

Telephone: 662-292-0160

Email: [email protected]

Forrest Bryan

Telephone: 662-202-8200

Email: [email protected]

Jared Spears

Telephone: 662-832-1393

Email: [email protected]

Elizabeth Dollarhide

Telephone 662-236-7551

Email: [email protected]

Jackie Beckwith

Telephone: 662-816-7632

Email: [email protected]

Lisa Harrison

Telephone: 662-202-2366

Email: [email protected]

News & Events

Don’t Miss a Thing: Connect with Us on Facebook!

Calendar of Events

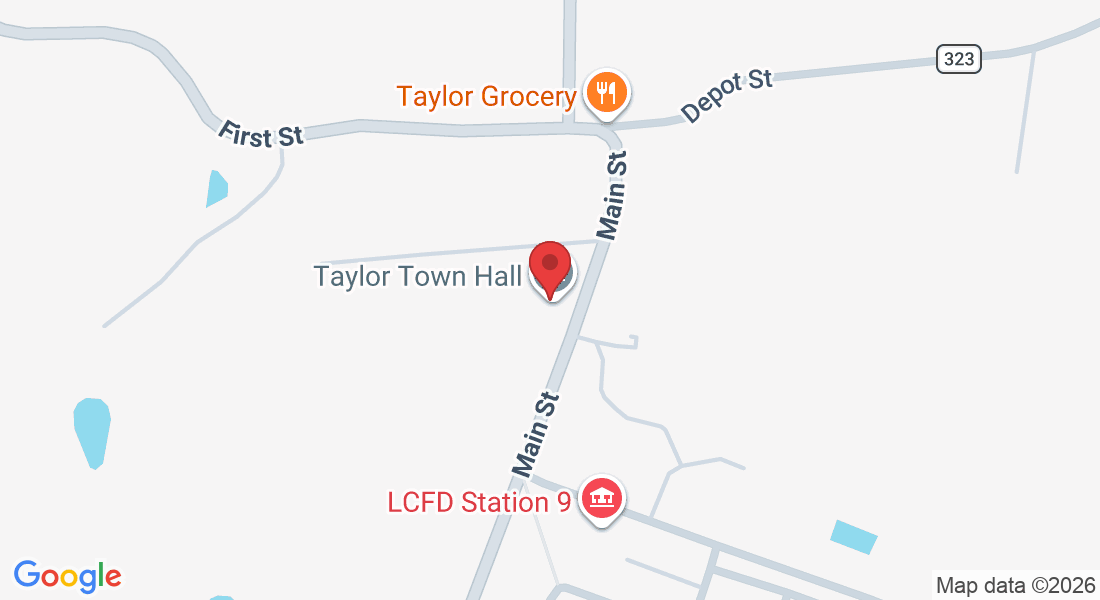

Rich in history and culture, Taylor encompasses about four square miles in the hills of north Mississippi and has about 320 residents.